Conceptual Framework

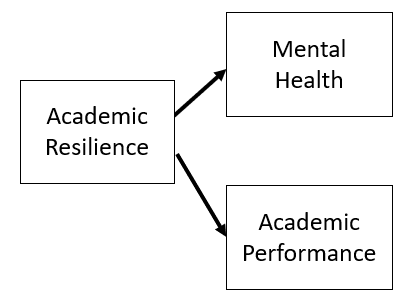

A diagram like Figure 1 is commonplace in postgraduate dissertations and theses. It may be called a conceptual or theoretical framework, depending on how wide (general) and how narrow (specific) they are.

Students of psychology, and many laypersons, would be able to list a few examples of mental health. In this case, mental health is a general variable with some possible specific variables like depression, anxiety, burnout, and panic disorders. In the same manner, academic performance is a general variable that can be specified in the form of CGPA, current semester's GPA, class test's score, assignment's grade, and other possible measures. Therefore, Figure 1 can be treated as a theoretical framework.

In this framework (admittedly a very simple one, just for a demonstration purposes), the scope is limited to the direct effects of AR to MH and AP.

1. The theory is silent about the factors that influence AR.

1. The theory is silent about the factors that influence AR.

2. The theory is only able to explain the direct effects of AR to MH and AP. It does not postulate any mediating or moderating effects to explain the relationship among the variables.

3. Though not clearly depicted in Figure 1, academic resilience is referring to an individuals' ability to bounce back from adversities. It is a personal capacity or trait. It does not refer to physiological processes, neurological activities, or other micro-level processes. Neither does it refer to the characteristics of a society, a team, a group, or some other social aggregates. This theory is about academic resilience at the individual level.

Notice also that the theory is built upon assumptions about the variables. The researchers may, for example, propose that academic resilience is a specific form of general resilience that can be measured. Until studies are actually done to show it as such, the box with Academic Resilience is only a theoretical idea.

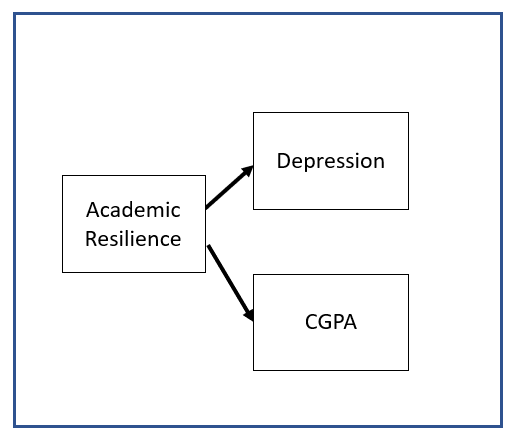

A student chose to focus on depression and CGPA for her thesis. She used Figure 2 as her conceptual framework. This chosen framework would guide her research design. Remember that the scope of the study is already partly determined by the theoretical framework. The conceptual framework provide further restrictions (scoping) of the study by focusing on specific variables.

The content of the conceptual framework is also relatively more quantifiable or measurable compared to the content in a theoretical framework. CGPA is a number commonly used as an index of academic performance (even though it may not be an accurate one). Depression is less straight forward; you need to identify the instrument (e.g. DASS, HADS, Zung Depression Self-Rating Scale) that will be used to measure (operationalise) it.

Based on the framework, we will develop hypotheses and determine the statistical analysis that would be performed. For example, we can hypothesise that 'AR is a significant predictor of Depression'. Notice that we don't use 'correlation' in the hypothesis. The arrow with a single head pointing to Depression suggest that the relationship is not bi-directional, which is what a correlational analysis would examine. Rather, we have a predictor variable (AR) and an outcome variable (Depression) which can be included in a regression analysis.

The framework also theorizes that Depression and CGPA are independent outcomes of AR. In other words, CGPA is not influenced by Depression. If we have reasons to think that the two influence each other (high CGPA leads to lower Depression, and high Depression can lead to lower CGPA) then we have to modify our framework.

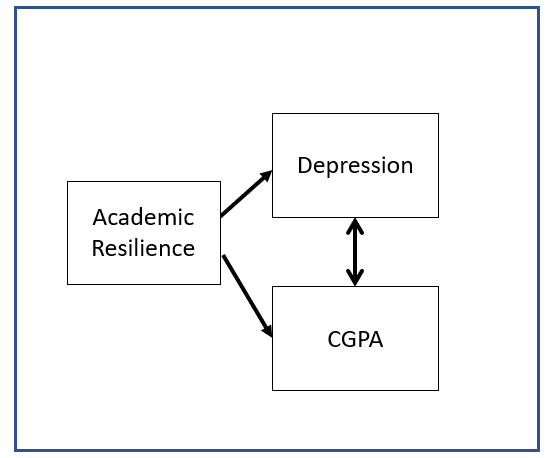

In Figure 3, the conceptual framework explicitly models the relationship between the two outcome variables. Therefore, we can justify testing another hypothesis: 'There is a negative correlation between Depression and CGPA'. We have a correlational hypothesis instead of a congressional because we have two-headed arrows connecting Depression and CGPA.

As the last point, remember that I mentioned there are at least 3 measures of depression. For a PhD project, let's say a student conducted 3 surveys, each one with a different measure of depression. The findings show that AR is related to Depression regardless of the measure used. A consistent set of results, right? If this is the case, then the student accepted all of the tested hypotheses that AR is related to Depression. Based on the accepted hypotheses, the student can then defend her thesis that AR is related to Depression. And that is how the specific results can be generalised back towards the wider theory.

If the findings are inconsistent (e.g. AR is not related to DASS, but it is related to HADS), then the student can conclude that the evidence is not sufficient to defend the thesis. She must provide some explanation and suggestions that may involve measurement issues or the framework itself.

If all 3 survey show a lack of relationship between AR and Depression, then she can make a case of modifying the framework. Consequently, she can revise the theory to (e.g. include mediating variable to see if AR influences Depression through another variable)

This short article does not do enough justice to the complexities of theoretical and conceptual frameworks. But hopefully, it had managed to trigger some points for you to think. So, what is your thought on it?

Comments